One of the clearest signs that Egypt is starting to reap the economic benefits of a currency float more than three years ago came last week. Nigeria, which took a different path when faced with similar problems, is still struggling.

Inflation in Egypt, Africa’s third-biggest economy, slowed to single digits for the first time since the pound was floated in late 2016. It had rocketed as high as 33 per cent soon after. President Abdel-Fattah El Sisi’s administration said a devaluation was needed to ease severe shortages of foreign exchange and get a $12 billion (Dh44bn) loan from the International Monetary Fund.

Though the decision was painful for Egyptians, it turned the Arab nation into a darling of bond and carry traders. And it set Egypt apart from Nigeria. Africa’s biggest oil producer was also suffering from a dollar squeeze, but opted instead to keep a tight grip on its currency via a system of multiple exchange rates and import restrictions. Foreign exchange is no longer scarce, but Nigeria’s inflation rate was 11.2 per cent in June — one of the highest levels on the continent — and has been above the central bank’s target of 6 to 9 per cent for four years.

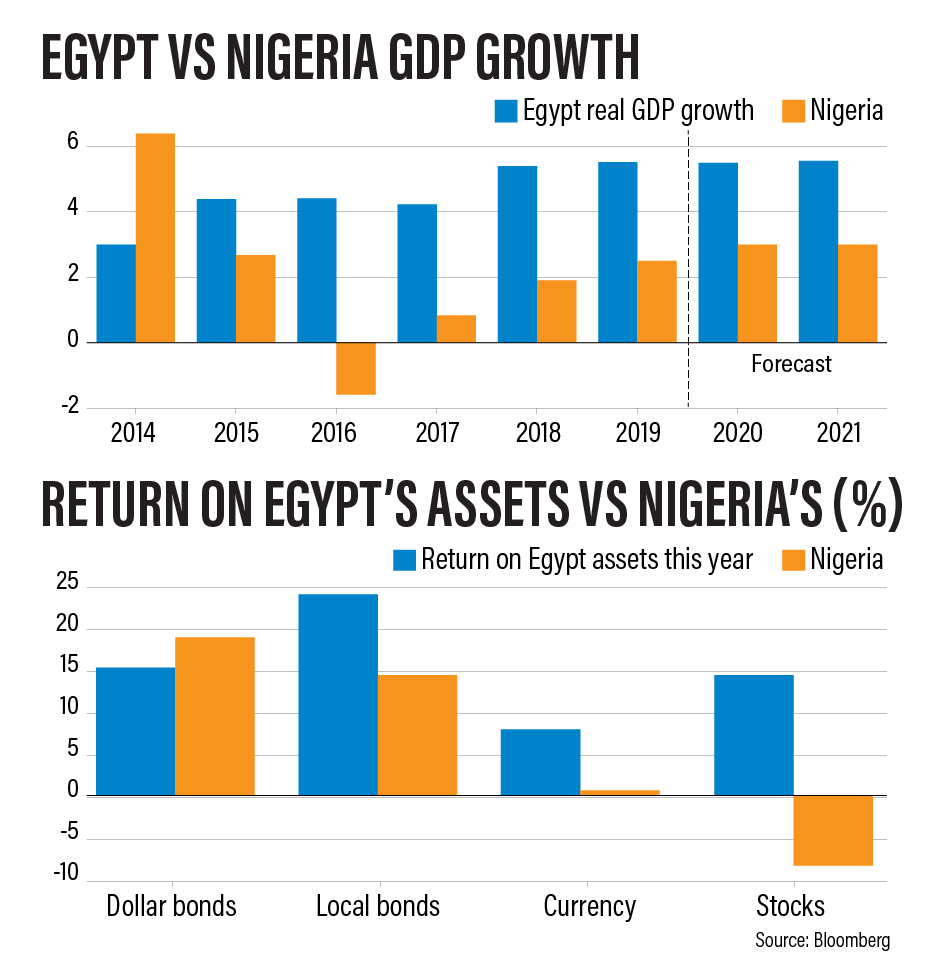

Egypt is also looking the healthier of the two in terms of economic growth. Its output will expand 5.5 per cent in 2019, more than twice as much as Nigeria’s and the most among Middle Eastern nations, according to Bloomberg surveys of analysts.

Portfolio flows into Egypt soared following the devaluation and the start of IMF-supported reforms, which included cutting subsidies that soaked up much of the budget. And it got more foreign direct investment last year than anywhere else in Africa, according to the UN.

Last month Egypt’s finance minister Mohamed Maait said his ministry aims to raise between $4bn and $7bn in the fiscal year that started July 1. The sales could include green bonds and Islamic sukuk as well as issuance in Chinese and Japanese currencies.

Nigeria has attracted plenty of hot money by keeping bond yields high and pledging not to let the naira weaken, but FDI has plunged.

The IMF says the Nigerian currency regime deters investors and hurts the economy, which is growing more slowly than the population. President Muhammadu Buhari argues it’s needed to boost local manufacturers and stop inflation accelerating.

Those hot-money flows and rising oil prices have caused Nigeria’s local and external bonds to perform solidly in 2019. But weak growth has turned investors off stocks. The main equity index in Lagos has lost 9.4 per cent in dollar terms this year, one of the worst performances globally. Egyptian stocks have fallen along with others in emerging markets since April, but they’re still up 13 per cent year-to-date. That’s partly down to the pound appreciating 8 per cent against the greenback, a performance bettered only by the Russian rouble.

Political and security risks remain high in both countries, according to Bloomberg Country Risk Scores. Egypt’s risk has climbed since Mr El Sisi came to power in 2014. His administration is trying to quell an Islamic State-linked insurgency in the Sinai Peninsula and has jailed tens of thousands of political opponents. Lawmakers passed a constitutional change in April that allows for him to remain in office until 2030. In Nigeria, which is also battling Islamic State militants and experiencing deadly clashes between farmers and herders, political risk is deemed higher.

Nigeria’s reserves have risen almost 9 per cent since late last year to $45bn. That gives central bank governor Godwin Emefiele plenty of firepower to defend the naira, which Renaissance Capital estimates is about 20 per cent overvalued. Still, stresses on the currency are rising, according to Citigroup’s Early Warning Signal Indexes. The opposite is happening with the pound. Analysts at Societe Generale said last week it could strengthen another 4 per cent to 16 per dollar this year.