Just as their economies had begun to recover from the man-made horror of coups and civil war, the West African nations of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone have been knocked back down by a terrifying force of nature: the Ebola virus.

In addition to the human toll — more than 4,000 dead so far — the outbreak has paralyzed economic life across the Ebola zone: shops closed, hotels vacant, flights canceled, fields untended, investments on hold.

In Conakry, capital of Guinea, stray dogs, goats and sheep are plopping down next to empty stalls in street markets devoid of shoppers.

About the only things people want to buy are products meant to guard against Ebola — antiseptic gels and devices that attach to faucets and add chlorine to the water.

Ebola facts: What you need to know

“These are selling like bread at the market,” said Cece Loua, who sells pharmaceutical products in Conakry.

The World Bank has dramatically downgraded its expectations for economic growth this year in the three countries hardest hit by the outbreak. Guinea will grow 2.4 percent, down from a previously forecast 4.5 percent, it predicts; Liberia, 2.5 percent, down from 5.9 percent; and Sierra Leone, 8 percent, down from 11.3 percent.

“It’s been really devastating,” said Rosa Whitaker, CEO of the consultancy Whitaker Group and a former U.S. trade official.

It’s an especially cruel turn for three impoverished economies that had been making steady progress after years of devastating conflict:

• In Sierra Leone, which endured a civil war from 1991 to 2002 that killed 70,000 and left 2.6 million homeless, the economy surged 20 percent last year and 15 percent in 2012.

• Liberia, which lost 250,000 people to civil wars from 1989 to 2003, has recorded double-digit economic growth four of the past five years.

• Guinea, with a history of bloody coups and political strife, has grown more slowly (2.5 percent last year and 3.9 percent in 2012), but had expected its economy to accelerate as foreign companies invested in such projects as the Simandou iron-ore mine.

“No one could have imagined the extent of the economic and social turnaround,” said Steven Radelet, a foreign-aid expert at Georgetown University and an adviser to the Liberian government. “The past 10 years, there’s been remarkable progress, and a lot of investors coming in.”

Ebola has frozen the economic revival.

“They were coming back and now have been set back in a big way,” said Francisco Ferreira, the World Bank’s chief economist for Africa.

The epidemic damages the economy directly. Commerce stops. The sick can’t work. Contaminated areas close down. Tax collections dry up. Health-care costs swell, squeezing governments already struggling with expenses.

But the indirect damage can be even worse as fear paralyzes Ebola-stricken communities.

“People are obviously very afraid of it,” Ferreira said. “People stay home and don’t consume. … Flights are being canceled because no one wants to go there. Hotels are firing people because no one is staying there.”

Liberia canceled soccer games because it’s “a contact sport, and Ebola is spread through sweat,” said Musa Bility, president of the Liberia Football Association. The suspension of sporting events has hurt Boima Folley’s sporting goods shop in the Liberian capital, Monrovia.

“No one comes to even ask for — let alone buy — sports materials these days,” he said.

Analysts are at least optimistic that the economic damage from the crisis can be contained to the hardest-hit countries. The three Ebola-stricken nations are economically small, and their troubles are unlikely to disrupt commerce beyond their borders: Combined, their three economies amount to half the size of Vermont’s.

Last week, the International Monetary Fund forecast that the 25 African countries it has grouped as “low-income” — including the three most hit by Ebola — would register a combined 6.3 percent economic growth this year, faster than the 6.1 percent in 2013.

One factor in Africa’s favor: Nigeria, West Africa’s dominant economy, and Senegal moved decisively to identify and isolate Ebola victims and those who had come into contact with them.

“We’re incredibly impressed by the ability of Nigeria and Senegal to keep their epidemics contained,” Ferreira said.

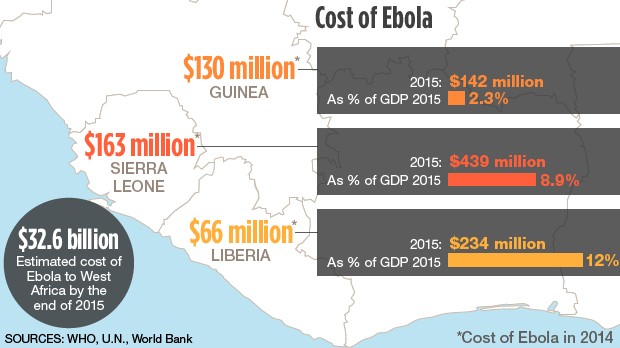

The World Bank still fears a worst-case scenario in which Ebola breaks out of three countries and spreads across West Africa. Under that scenario, economic losses across West Africa would rise as high as $32.6 billion this year and next, up from no more than $9 billion if the disease were contained.

Continent-wide, Africa has made significant strides. Six of the world’s fastest-growing economies are in Africa, the White House reported at an August U.S.-Africa Summit meant to celebrate the continent’s rise.

Most analysts think Africa’s overall economy will continue to expand. The momentum remains strong, and damage from Ebola still seems likely to be contained.

“I don’t think there will be lasting damage,” said Anna Rosenberg, head of Frontier Strategy Group’s sub-Saharan Africa practice. “The growth story coming out of sub-Saharan Africa is too big and too real to be ignored. There’s nothing that is going to stop it going forward.”

In the U.S.

Economists say global troubles aren’t enough to derail a U.S. economy that’s gaining strength from a stronger job market, falling fuel prices, lower mortgage rates and stronger household finances and confidence.