Women in Nigeria often turn from victims into abusers in this endemic and complex human trafficking crisis that leads all the way to Europe.

The woman sitting before us in an interview room in Benin City’s anti-trafficking headquarters cuts a slight figure. Faith, aged just 25, shuffles her feet nervously, her head bowed.

She is not what you expect to see when you’re told you’re to meet a people trafficker.

Of all the shocking aspects of Nigeria’s endemic human trafficking crisis, this is perhaps the most chilling: that it is very often a crime against women perpetrated by women, themselves desperate to escape destitution. More than half the beds in the cells here are reserved for female suspects.

Faith was caught trying to take three other women, one of them her sister, out of Nigeria to Burkina Faso. It was the same route along which a trafficker took her, she says, before he forced her into prostitution.

Faith took the business model and turned herself from victim into abuser, exploiting desperate women from her own community, but now she faces a prison sentence.

“When I first came back [home] they asked me what I was doing there – I told them I was a hairdresser, I couldn’t tell them I was a prostitute.

“I told them I didn’t want to take anybody – but they begged me. What I hoped to achieve was to make enough money to open up a shop back here at home.”

This disturbing encounter highlights one of many complexities of the fight against modern slavery in Nigeria, whose human trade routes snake out of Edo state across Africa and into Europe.

The traffickers have taken such a grip over this part of the country that 92 per cent of all women taken to Europe from Nigeria for prostitution come from Edo state. In the past year, the UK alone has seen a 31 per cent rise in the number of Nigerians being trafficked.

That is why Kevin Hyland, Britain’s new anti-slavery commissioner, is making Nigeria a key focus for his work – and why last week he was in Edo state devising a strategy of education and investment.

The dangers are clear and the challenges stark. So interlaced are the criminals with their communities that just 19 traffickers have been convicted here in the past 12 months.

“Across the globe at the moment there are more people than ever who are displaced, whether through natural disasters or conflict,” Mr Hyland, the former head of the Metropolitan Police’s trafficking unit, says.

“But there are criminals who are using that as a way of earning money. They are turning people into a commodity – so they have to be targeted in an organised way.”

He knows there will be women from this part of Nigeria on the streets of Britain tonight, coerced and controlled by their traffickers.

“It’s people from this very spot where we are now who end up being exploited in our towns and cities – it’s very important we treat this very seriously and respond to it here in Nigeria so we can prevent it happening in the first place.”

He addresses a community in a rural village, a crowd of elderly people many of whose families have fallen for the traffickers’ promises of a better life in Britain – and are horrified to learn their daughters may have been forced into sex work.

Even basic education about the crime could make a difference here. But one reason this message rarely gets out is that those victims who do manage to flee their traffickers hardly ever return to their communities, such is the stigma attached to prostitution and coming home empty-handed.

In a squat building behind barbed wire in the backstreets of Benin City, one young woman tells us of her shame. She is in the secret care of a shelter run by Roman Catholic sisters, after escaping her female trafficker who had taken her to Italy and forced her into prostitution. She had had to sleep with as many as 20 men a night.

“My madam beat me up. She used a razor blade to cut my body,” Precious says. “She would not give me food to eat. She took my passport and my phone and I was unable to talk to anybody.

“Each time I would go to work and come back, each time I entered the house she would tell me to pull my clothes off for her to be sure I didn’t hide any money.”

And her trafficker had secured yet another bond with her victim. Before leaving Benin City, she had taken Precious to a Juju man, to perform an oath of loyalty between them. It had left Precious terrified a curse would fall on her if she escaped – yet another layer of bondage in Nigeria’s slave trade for the authorities to try to sever.

Precious raises her hand to her head and pulls off her hair. Underneath her wig, her skull is almost bald. She is convinced the Juju is to blame.

“It was the oath that I took – this is the result,” she sobs.

“I wouldn’t even pray for my worst enemy to experience this – it is so painful. Ever since I have come back it has not been the same, I have been fighting one battle and then another.”

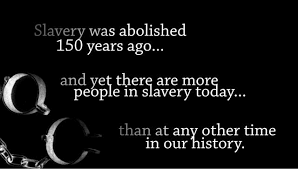

Precious may be one of the fortunate ones who managed to escape but is far from free yet. The physical chains of old fashioned slavery may have disappeared into history – but as both Britain and Nigeria grapple with its modern incarnation, the psychological and emotional shackles are surely as powerful and as potent.

Source: Julie Etchingham reports from Nigeria on the trafficking trade for ITV News at Ten on Thursday Oct 14 and Friday Oct 16.